For assistance, contact your mainland vet in Somers Point at (609) 653-1800 or reach out to Cape May Courthouse at (609) 465-0404.

Color Blindness & Amsler: Vision Tests

What is Color Blindness?

What is Color Blindness?

What is Color Blindness?

Color blindness, or color vision deficiency, means you have trouble distinguishing certain colors because the cone cells in your retina don't work properly or are missing. The most common forms are red‑green deficiency (protan or deutan) and blue‑yellow deficiency (tritan). Rarely, people have complete color vision deficiency and see no color at all. Symptoms include difficulty telling the difference between shades of red and green, green and blue, or yellow and blue, trouble matching clothing, and problems recognizing how bright or saturated a color is. Most people inherit the condition; risk factors include being male, a family history of color blindness, certain eye diseases like glaucoma or AMD, chronic illnesses like diabetes or multiple sclerosis, and medications. There's no cure for genetic color blindness, but adaptive strategies and assistive devices can help you function confidently.

Symptoms & Causes

What is Color Blindness?

What is Color Blindness?

Color vision deficiency often causes difficulty distinguishing between shades of red and green or blue and yellow. You may see colors as duller than they are or struggle to judge how bright or saturated they are. Most cases are inherited due to mutations in the cone pigments, especially on the X‑chromosome, which is why it affects men more than women. Other causes include eye diseases like cataracts, glaucoma or macular degeneration, brain or optic nerve injuries, chemical exposures and certain medications. There is no cure for genetic color blindness, but early diagnosis and adaptive strategies can help; experimental gene therapy is being studied for rare achromatopsia.

Diagnosis & Monitoring

What is Color Blindness?

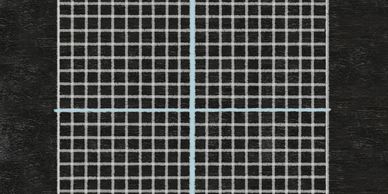

Amsler Grid Test Instructions

Color vision deficiency is diagnosed during a comprehensive eye exam. Your ophthalmologist will use tests like the Ishihara color plates, arrangement tests such as the Farnsworth D‑15, an anomaloscope or computer‑based assessments to check how well you recognize different colors and hues. There is no cure for inherited color blindness; most people adapt by learning alternative cues and using color‑identifying apps or labels. If your color vision changes because of an eye disease or medication, treating that condition may improve color perception. Patients with macular degeneration should also monitor their central vision using an Amsler grid and report any new distortion or dark spots.

Amsler Grid Test Instructions

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

Amsler Grid Test Instructions

An Amsler grid helps you check your central vision at home, especially if you have macular problems. Hold the grid at your usual reading distance in good light while wearing your reading glasses. Cover one eye and focus on the center dot without moving your gaze. Notice whether the straight lines appear wavy, blurry or if any boxes seem missing or dark. Repeat with the other eye. If you see any new distortion, blank spots or changes, call your eye doctor right away.

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

While there is no cure for inherited color blindness, many strategies can make life easier. Label clothing or arrange your wardrobe by color and rely on patterns, symbols or the position of lights rather than the color itself. Ask friends for help or use smartphone apps and special glasses or filters designed to improve color discrimination. Discuss adaptive tools with an eye care professional; with support, most people with color vision deficiency can perform everyday tasks, drive safely and enjoy independent lifestyles.

Support & Resources

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

Living with Color Vision Deficiency

We provide resources and support for people living with color vision deficiency and their families. Our team offers genetic counseling to explain inheritance patterns, refers you to low-vision specialists, and suggests smartphone apps that identify colors or adjust contrast. Specially tinted glasses or contact lenses may also help some people distinguish colors more clearly. Our goal is to empower you with tools, information, and personalized advice so you can navigate daily life confidently.

Copyright © 2025 | Mainland Eye Center

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.